The Great War is dragging on. As the festive season approaches, Brighton is doing her best to show her support for Britain’s French Allies. On 16 December 1915, the Brighton and Hove and South Sussex Graphic certainly gave France pride of place.

In the newspaper, a journalist simply called Aigrette pens a splendid article about Madame Adolphe and her French ladies’ tailors in Preston Street. At this emporium “the reducing pencil has been hard at work and lovely bargains are on sale”. Aigrette is mightily impressed by one outfit: “a triumph of fashionable elegance.”

Alas, to our, fortunately, greater sensitivity to these matters in the 21st century, the cloth is shockingly described as “tête de nègre velour cloth of beautiful supple quality.” It is unlikely that in 2023 any fabric would be compared to a black person’s hair, however supple it may be.

In 1915, it is considered unpatriotic for a lady to wear one of those hats they make so well in Austria, and anyway, such hats “are not likely to visit our shores for years to come.” Never fear, ladies. “Madame Homer Herring has filled the gap, and has a splendid assortment of French velour hats, direct from Paris.”

But Madame Herring can do one better: “amongst the flowers, feathers and dainty fabrics” that you would expect to see in the window of any self-respecting milliner there was another item… “the helmet of a German non-commissioned officer, picked up by her son , Lieut. Homer Herring … in Flanders.”

On a more serious note, reports back from that same Flanders field vary in their enthusiasm for the French and French soldiery.

Three reports show the considerable prejudice in Britain against what was seen as the over-emotional nature of the French.

At a lecture in Hove Town Hall on 11 December, Lieutenant George E. Pitt B.A., F.R.G.S. starts his talk by admitting that he “went to France, expecting to find the people hysterical, without any solid basis [for his view]” and that he “was not prepared to suppose that they would be able to rise to such an occasion.” (Brighton Herald)

In the Graphic, a military engineer reports from a (necessarily) unnamed town in rainy Flanders. He adopts the name of Caoutchouc … for the simple reason that he is so pleased to own a pair of waterproof boots made of rubber (caoutchouc). Life is not all work and no play this far behind the front line. The village in which he finds himself still has functioning cafés and bars. Our magnificent French Allies have their feet of clay, however:

“In the evenings, there were cafés and estaminets, quietly homely places crowded with exceedingly well-behaved militaires (as our Allies call us) … The inhabitants were cheery enough and good to us after their kind – a very long way after their kind – for their practice is to charge an Englishman double the toll extracted from a pimpion or a civilian. Khaki uniforms, designed to render the wearer as inconspicuous as possible, here fail in, or completely defeat, their object, for they (the Frenchmen) seem to spot us coming from afar and up go the prices.”

Caoutchouc goes on to define a pimpion as an unpaid French soldier.

In the same edition of the Graphic, a certain Mr. Frederic Villiers analyses our French Allies: “when you consider the French character with its dash and go … It has always been easy to get them up to a point where they can make a magnificent rush on the enemy, but the difficulty, one would suppose with the quick French temperament would be to keep them still under the severe strain of trench warfare.” But, and there is a “but”, Mr. Villiers gives much credit where credit is due: “… it is wonderful what the French troops have done. … They can remain perfectly still for weeks and months and be quite fresh when the time comes to move forward.”

In much the same way as Mr. Villiers, both Lt. Pitt and Caoutchouc have reason to revise their opinions.

As Caoutchouc nears the front line, he is billeted in a very humble cottage: “Our second day here was enlivened by a Taube raid, and similar aerial bombings have occurred frequently during our stay here. The populace take no notice of these little affairs. They merely glance upwards at the cause of the disturbance.”

And far from being hysterical, a solider in a hospital shows Lt. Pitt more than just resignation: “In the operating theatre I encountered a man who in the midst of his great agony would accept no sympathy. Ce n’est rien, monsieur, he said, c’est pour la France.”Lt. Pitt cannot speak highly enough of French patriotism and stoicism.

In the realm of entertainment, Mrs. Maxwell Davis, a wealthy socialite, is doing her best to support the Belgian wounded soldiers. She has devised and mounted a play in French in her own front room.

This room, at 11 Wilbury Road, looks rather small to put on a play. Mrs. Maxwell Davis must have been aware that the vast number of Belgian refugees and most of the wounded Belgian soldiers in Brighton were Flemish speakers and would not have understood French. The audience would have been very small … and possibly for officer only – the ones more likely to be French speaking.

At the end of the concert, Pastor Joye “emphasized the fact that the Church, although Protestant, makes no distinction of creed, being truly a sister Church to all in need.” A tradition of bringing comfort to French speakers which continued in the little church until it closed 90 years later.

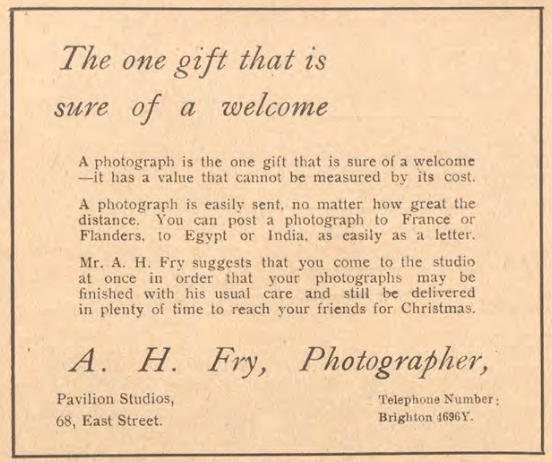

Photographer A.H.Fry also knew that a portrait from home would comfort British soldiers in France.

But beyond all the entertainment, frippery and humour in the Brighton Graphic and the Herald, how could the bereaved and the anxious at home be comforted? The main thrust of the Graphic newspaper was to pay tribute to local soldiers fighting in France. The 16 December 1915 edition of the Graphic lists a Roll of Honour of twenty-eight Brighton men serving in the forces. Of the ten whose whereabouts are recorded, five are in France and one has just been killed at the Battle of Loos. It also tells the story of Mr. S.S. Pettyfer (hosier of St James’s Street, Brighton) and his pride in his nine nephews and eleven cousins serving their country. He is still mourning the loss of two nephews, one of whom has died at sea, the other died in Paris of his wounds.

Never, perhaps, was Brighton so close to France as during the Great War.