France is so near Brighton. Hundreds of Brightonians take the short hop across the channel in order to walk or cycle, usually in the French countryside. Sometimes in towns. However, at the turn of the 21st century, three Brightonians left a record of their visits in book form. Each one is fascinating in its own way. In order of publication:

1. 1994

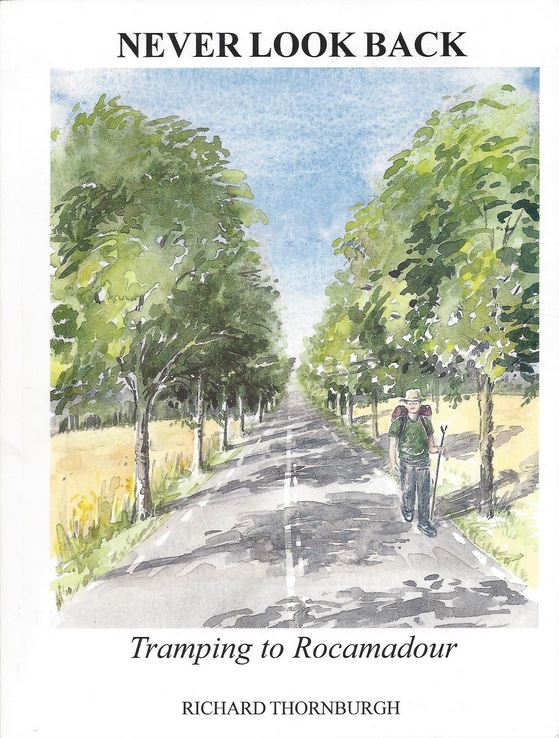

The Rev Richard Thornburgh was Brighton born and bred but his service to the church as an Anglican priest took him to Beaminster in Dorset. It was from here that he set out to walk the 636 kilometres (sounds even more daunting than a mere 397.5 miles) to Rocamadour. Why? Part pilgrimage, part fund-raising exploit, part personal challenge. All excellent reasons for going.

As the reader follows the journey across France, Richard always makes clear where exactly he is. Each chapter has a delightful line-drawing map by the author. The style of writing is measured and purposeful but not in the least over-serious. Although the route was across country, avoiding large towns, Richard kept mainly to the very minor D (départemental) roads. This made for a quieter life on these less used roads and signposting was adequate. However, some of the perils of the open road might surprise the reader. They certainly surprised Richard.

Characteristic extract: “I awoke to Tuesday morning and the seven o’clock chimes from the church, convinced I had already heard them once as I was surfacing to consciousness. It was pouring with rain, so I stayed in bed for another forty-five minutes.”

- Did the church clock really chime twice? Richard does eventually explain.

- Yes, it rains in France in early May. As with all three books this is a ‘warts and all’ view of France.

- If it’s raining outside, stay in bed as long as you can! Good, common sense.

2. 2004

Oliver Andrew is a Brightonian by adoption but has lived in the city and taught French locally for many years. In 1999, the “sluggish and prosaic onset of retirement” challenged him to walk from Dieppe to his father-in-law’s village in the Pyrenees. Oliver modestly slips in the fact that he was also raising money for Brighton’s Alexandra Hospital for Sick Children.

There is only one single map showing the daunting length of the trip, but it does reveal that the walk must have been well in excess of 1000km. Oliver’s approach to the journey was almost the opposite of Richard’s. Roads of any kind were to be avoided at all costs. The GR (Grande Randonnée or long distance) paths were the thing. Oliver’s writing style very much matches the ‘off-the-beaten track’ nature of the walk itself: a long detour around fallen trees might lead to a musing on the origins of the concept of pays (my village, my area, my county, my country) or an enforced rest in a bar (dodgy hip) elicits an analysis of different kinds of mushroom to be found in the particular area.

Characteristic extract: “In one village, a farm still bore plaques celebrating prizes won at cattle shows in the 1920s. The local breed, the Parthenay, is known for its qualities as a meat- and milk-giver, but it is famous for its butter. At one point, the path headed for a crane, which turned out to be a motorway under construction.”

- Oliver teaches us a great deal about the parts of France he passes through.

- There is a strong sense of la France profonde and its progress toward modernity.

- And if you want to know the 18 vital uses of a staff or stick on such a walk, you need do no more than read Appendix A

3. 2004

Rob Silverstone has a spent much of his life working in Brighton as restaurateur and lecturer. His adventures do not extend beyond Upper Normandy, but, as a former resident of Rouen, his account concentrates on depth rather than breadth in his analysis of contemporary France. Indeed, having opened a restaurant in Rouen, and having battled all the attendant bureaucracy, it can truly be said that he did “discover” Upper Normandy.

As a keen cyclist (and perhaps slightly less enthusiastic walker) Rob revels in the delights – and horrors – of towns, villages and countryside. Of the three books described here, this is the only one which occasionally alternates between life in France and life in Brighton, so although the book was written than 20 years ago, it is still a fascinating glimpse of the recent past of each place, especially as Rob is able to point out similarities and contrasts.

Characteristic extract: “If you ever need to use Rouen coach station (n.b. 2004), time your arrival just before departure, because it is a bleak dispiriting place, a bunker filled with engine fumes. Pacing up and down, you strive to construct an image that will take you out of this place, but the grey torpor takes hold … (same page) Tournedos has a tiny town hall that must have been built by children.”

- Punches are never pulled.

- Throughout the book there is an imaginative turn of phrase that delights the reader.

***

All three books are captivating as the reader really comes to know the personality of each writer – his travails, his delight in France and his reactions to the situations in which he finds himself. Each book will teach even the most ardent Francophile something new about France or the French.

The books vary above all in their style of writing. Richard’s book is the one to read from start to end as it draws the reader in to the relentless, day-after-day trek (via joy and despair) before reaching its spiritual climax in Rocamadour. The other two books are wonderful for dipping in to. Rob’s knowledge of and delight in French traditional food is infectious. Oliver’s knowledge of French literature and history is both wide and deep.

Are there any more books of this sort out there by Brightonians? It would be great to know.

All three books are available on the Internet. Prices for each book vary tremendously, so do shop around.

They do say that the best way to come to know a country is by travelling through it on foot. Though I have travelled to widely in France, I have never been bold enough to emulate these three hardy gentlemen and to rely on Shanks’ pony.

I wonder whether the Rev Richard Thornburgh was, consciously or unconsciouusly, imitating the great pilgrimages of te past as described by Chaucer and others.

I am sure that these works will be of interest to historians, geographers and social scientists, as well as humanists, and that their value in these fields will increase rather than dominish with the passing of time.

LikeLike