“Ah, well, there’s one good thing,” continued Sukie, rubbing the tea-caddy with her apron, “stranger he is, but he’s not one of them nasty French critturs.”

Sukie was a maid-of-all work depicted in a fictionalised account of the Hine family. The account represents the attitudes toward France during much of the early to mid-nineteenth century.

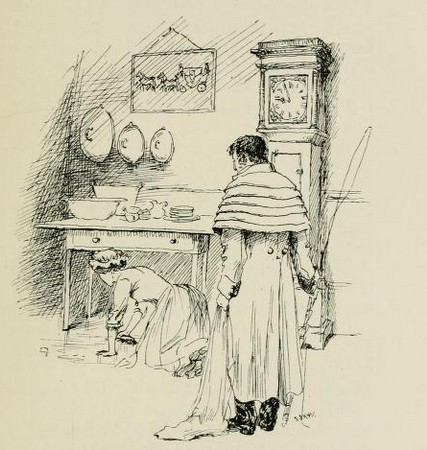

Sukie watched over by her master, Mr Hine. Illustration by Lucy Kemp-Welch from “Round About a Brighton Coach Office” by Maude Egerton King. Published 1896

Maude Egerton Hine King, who created the character of Sukie, was the granddaughter of William Hine. Mr Hine had moved to the burgeoning town of Brighton in about 1798. There, he set up in East Street as a coach proprietor. He never made a fortune (hence only one servant) and had been more or less put out of business by the time he died in 1846. The male narrator put it graphically in the novel:

Loss followed on loss, and trouble on trouble. The first railways between London and Brighton was opened and that railway cut right through the livelihoods of many families, our own among many others.

But back to Sukie and what the narrator describes as “the last teens of this century” although in fact most of the events seem to take place during the reign of George IV (1820-1830).

“I don’t know if it’s rude or not” Sukie said, obstinately, “but true it is ; any one as don’t squint could see at a glance that they ain’t like us ; they look quite different ; they ain’t natural, to my mind. And, then their silly ways ! I’ve no patience with them to hear them jabberin’ their nonsense at you …”

However, William Hine’s sons and daughters had been brought up to be ladies and gentlemen. As young people of the tradesmen classes, they had been educated and had travelled.

Sukie is quite distressed by the fact that her young masters and mistresses can reply to this jabberin’ in these people’s own tongue. Sukie continues to the narrator:

“… and you jabberin’ it back again – it do rile me !”

It transpires that ties with France were far closer than they had been during the Napoleonic wars, at least for the middle and upper classes. Sukie’s comments reveal that the servant and labouring classes were not yet ready to forgive the French.

The Hine home often had French visitors, possibly because two of the sons had worked in France and could speak French. According to the narrator:

“The little packet from Dieppe not infrequently brought us a visitor at that period, for my brother had been in France and had formed several friendships there.”

Illustration in “Brighton, Scenes Detachees d’un Voyage en Angleterre by Le Comte A de la Garde” 1827 Courtesy of Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

It is highly likely that these were trade relations. In the novel, the mother of the family runs a small glass and chinaware shop. The son or sons may have travelled to France to source stock for the shop. It is unlikely they were involved in smuggling – but smuggling from France impinged upon each and every household in Brighton.

“There was not, I believe, a housewife in all the town but knew where to get her tea and brandy without paying duty, not a lady that had not learned the trick of considerably reducing the outlay of her pin-money over ‘real French fineries”. Without curtailing her socks of silks and laces at all.” [The area around Lyon in France was the major European producer of silk, required in England as both cloth and as essential sewing thread.]

Mrs Hine is no exception to the rule. She is visited in her kitchen by a pedlar woman. The crone asks:

“What would you say to a little flask of French brandy ? or a bit of baccy for the good man, m’lady ; eh, my dear ?”

The narrator then goes on to reveal that it was not just people such as the Hine family who were benefitting from and supporting smuggling:

But if we little people fostered the smugglers’ trade the great folk came no whit behind. It was an open secret that every extra fine consignment from the Continent found its way first to the Pavilion, that the King might skim the cream off it ; while in more than one instance, the poor fellow that brough it over was fuming his heart out in Lewes gaol.

The girls of the family seem, however, to be particularly Francophile. One of the narrator’s sisters, Mary, was clearly devoted to the French language. Mr and Mrs Hine had clearly seen education as important for their children. To some extent this caused a minor rift or educational divide between the generations: Mrs Hine was a superb but simple housewife and shopkeeper, her husband a coachman in trade, running his own business. The children were more sophisticated. Speaking of his mother, the narrators says:

Having received little or no education herself, she could ill sympathise with Mary’s tastes, and was sometimes a little short with her on the subject. But then she grew inconsistently proud and pleased when the clergyman commended Mary’s gifts, and wished she had such a tongue for French as she [Mary].

When a certain Mr Trevanion came a-wooing of Mary, part of his appeal to the young girl was that

he took great delight in the French language, and sang charming songs in that tongue to his guitar in the evenings.

Indeed it looks as if sometimes Mr. Trevanion and the Hind girls took advantage of the fact that Mama had no knowledge of French. French was not only romantic, but an ideal way to conceal a courtship being carried on in plain view:

… very helpless and alarmed my Mother felt one time, when Esther, the only one of us beside Mary who knew what the words were about, broke out into a ripple of laughter, while Mary bent her head lower over her work, and stitched away with more than her usual energy.

Song score published in 1824. Source Gallica.bnf/Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Alas, in this case it was Mr Trevanion and not a Frenchman that Sukie should have called a “critter”. Mary had fallen in love with the young Englishman, he had proposed marriage … and then vanished without trace.