What brought Edouard Victor Lacroix and his French wife, Mary, from Jersey to settle in Brighton? In Jersey, Edouard had been a locksmith and then a tin smith. Mary dealt in local produce. When the couple arrived in Brighton in the very early 1860s, the town was burgeoning. There must have been plenty of work for a man with Edouard’s skills, and yet by the end of the decade he had adopted his wife’s trade and settled with her and their expanding brood of children at 12 Bartholomews.

12, Bartholomews (middle house) now vanished under the north side of the Leonardo Hotel. Image courtesy of the Regency Society (James Gray Collection) JG_09_047

Edouard’s eldest son, Auguste, had been apprenticed to a cabinet maker in Jersey. There must have been many opening for the lad in Victorian Brighton at a time when there were nearly 30 cabinet makers in the town. But no, both Auguste and second son Louis Victor were draw into their father’s trade of importing ‘foreign goods’ namely eggs, potatoes, (think of those delicious Jersey Royals), fruit, poultry and butter.

Initially, the business did not seem to do well. In February 1868 Edouard was on the verge of bankruptcy, owing over £200.00 with only £39.00 in the bank. “Cause of failing” according to the report in the Brighton Gazette, “Dullness of trade, and expenses of my family exceeding my profits.” By this time the couple had nine children.

Disaster seems to have been averted. Mrs Lacroix was, much later, described by the Globe newspaper as “practically the mainstay of the family”. It would seem that she frequently travelled to Paris “for the purpose of buying garden produce and importing it to England, to her husband, who has carried on an extensive business as a fruiterer in Market Street, Brighton, for many years.” It may be that she also ran the sales side of the business with her sons.

All five daughters married well, three of them also trading as fruiterers or florists either alone or with their husbands. Of the four sons, all were at one time assistant to their father.

The two best known sons locally were Louis Victor and Albert Pierre, both born in St Helier, in 1851 and 1862 respectively. Both became leading lights in the Brighton Volunteer Fire Brigade (BVFB). This brigade was quite separate from the paid Police Fire Brigade. It was run very much on the same lines as the Royal National Lifeboat Institution is still run today: donations paid for equipment and expenses; the men gave their part-time service for free.

Louis Victor Lacroix rose to be superintendent of the paid Police Fire Brigade – on starting his new post in 1888 it was at the grand annual salary of £150.

Brighton Volunteer Fire Brigade Station, 4 Duke Street, Brighton (1922). Telephone number: Brighton 3 (from about 1900 onward). The mustachioed man at the front seems to be Louis Victor Lacroix. Image courtesy of the Regency Society (James Gray Collection) JGC_08_026

Lacroix was a very plucky and inventive man and clearly had links with French brigades. The BVFB, perhaps thanks to Lacroix, was frequently invited to visit France. The first of these visits was in 1889. The Exposition Universelle [The Paris Exposition] was in full swing and the French wanted to show off their new Eiffel Tower.

The newspaper, Le Soir, is laconic in its report:

« Une députation de sapeurs-pompiers volontaires de Brighton, appelé London super mare, a visité aujourd’hui l’Exposition et a fait l’ascension de la tour Eiffel …Les membres de cette brigade, au nombre de trente environ, sont à Paris depuis samedi. Dans les divers établissements qu’ils ont visités, ils ont été accueillis avec une parfaite courtoisie. » [Today a delegation of volunteer firemen from Brighton, known as London super mare, visited the Exposition and ascended the Eiffel Tower … The thirty or so members of the brigade have been in Paris since Saturday. They were received with utmost courtesy at every institution they visited.]

In contrast, the reporter from the Brighton Herald who accompanied the group waxed lyrical … covering more than two extremely long columns in his newspaper. His main impression was that the French were very curious about their visitors:

“the brigade absorbed universal attention …At least a hundred times in a single day one of the party, – who by virtue of a previous acquaintance with the French capital was entrusted with the pleasant duty of leading the others from point to point, – was asked point blank who were ‘Ces messieurs là’. Was it Lacroix who was guiding the party?

The sightseeing schedule would have exhausted the fittest athlete: the brigade were shown the Louvre, Notre-Dame Cathedral, les Halles centrales (equivalent of Covent Garden produce market), the commemorative column on the Place de la Bastille, the Grand Opera House and, of course, the Morgue which was, apparently, just behind Notre-Dame.

Superintendent Lacroix was constantly looking for ways of improving the Brighton fire service – he was, after all, responsible for overseeing many of the fire precaution arrangement in public buildings such as the Theatre Royal. At the Opera House in Paris (now le palais Garnier), Lacroix inspected the fire security arrangements. He is reported as saying: “as far as the fire appliances are concerned, I could not find any improvement on what I have seen in England.”

A delegation of French firefighters visited London two years later. A syndicated item in several French newspapers reported on their visit to Brighton on Friday 26 June 1891:

Une belle réception avait été préparée, à Brighton, pour des pompiers français. Des brigades de pompiers de diverses localités du comté de Sussex les attendaient à la gare pour les conduire à la salle Madeira, où ils ont été présentés au maire et à sa femme, ainsi qu’aux conseillers municipaux. [In Brighton, a fine reception had been prepared for the French firemen. Fire brigades from various parts of Sussex met them at the station and accompanied them to Madeira Hall [translator’s note: most likely, the Aquarium]. There they were introduced to the mayor and his wife as well as to the town councillors.]

The next day, the Brighton Gazette could not contain its excitement about the visit. The account ran across four immensely long columns. It included not only a blow-by-blow account of what the French guests saw and did, but even the menu (all in French of course) for the gala lunch in the Banqueting Room of the Royal Pavilion. The name of Superintendent Lacroix does, of course, figure in the list of attendees. The Mayor gave a toast in French and le Capitaine Davis from the French contingent replied in like manner. Both speeches were reported verbatim, with translation.

Louis Lacroix’s connections with France did not wane. In 1895 he was awarded “a silver medal and diploma, received from the President of the French Republic, to Fire Superintendent Lacroix in recognition of his gallantry at fires.” Alas, the award was not received from the Président himself but via the Mayor of Brighton.

It would seem that the good burghers of Brighton were not keen to let their one of their top firefighters pop off to France too often. In mid-1900 the President of the Fire Brigade Officers and Sub-officers of France and Algeria requested that a detachment of the Brighton Police Fire Brigade take part in the international competition to be held in Paris that year. The Watch Committee resolved that it “Could not comply”. The same committee also refused Lacroix permission to attend the International Fire Brigade Congress to be held in Paris in August in 1901.

Lacroix did not give up trying to forge closer relationships with France …

By 1911, attitudes seem to have softened within the Watch Committee (perhaps it had new, more open-minded members). When Superintendent Lacroix was invited to attend the Fédération des Sapeurs Pompiers Français [Conference of the Federation of French Firemen] to be held in Paris and Tunis in August, the Superintendent was given leave of absence for one week. There was no mention of paying him while he was ‘on leave’ representing his town and his country.

There was a sad interlude in Louis Victor’s life in the late 1880s, just before he was promoted to Superintendent.

One Saturday evening in February 1886, young Albert Lacroix had returned home feeling unwell. He stayed in bed all day Sunday. By Monday morning, the 24 year-old lay dead in his bed. Death was from natural causes. He had had typhoid fever a couple of years previously which had perhaps weakened his heart. The funeral was impressive as befitted a well-respected and brave firefighter. Albert’s coffin was draped in the Union Jack, and in addition to several wreaths, it was “surmounted by the deceased’s silver helmet, tunic, belt and axe”. The coffin was carried from 12 Bartholowmews by six of his colleagues and then placed upon “the manual fire engine” drawn by four horses. The carriage was preceded by “the band of the Railway Fire Brigade, playing the ‘Dead March’ in Saul”. Crowds thronged Bartholomews and the whole route to the Parochial Cemetery (now the Woodvale Cemetery). As the cortège passed St Peter’s Church “the bell was tolling in token of the occasion” … a signal honour from a Church of England establishment as the deceased and his family were Roman Catholics. Edouard and Mary had lost their youngest son. Louis had lost his brother and colleague.

Although this photograph was taken in Hove some 30 years after the death of Albert Lacroix, it gives a good idea of the turnout on the death of a fireman or policeman. Image courtesy of the Regency Society (James Gray Collection) JGC_14_072

Fourteen months later, late on Tuesday 12th April, Mary Lacroix, Louis Victor’s mother, boarded the paddle-steamer Victoria at Newhaven, bound for Dieppe. She was off to Paris to source more produce for the business at 12 Bartholomews. The ship set sail and made good time, arriving to within about a mile of Dieppe Harbour in the early hours of the following morning. Fog swirled around. Lack of signals from the nearest lighthouse led the experienced Captain Clark to lose his bearing. At 4.00am, in the breaking dawn, the PS Victoria crashed onto the rocks of the Point d’Ailly. On board were 90 passengers, one of which was Mary Lacroix, aged 61, as well as 30 crew. The final death toll was never completely established, possibly it was as many as 16, but there is no doubt that Mary Lacroix perished in the disaster. The bodies of Mrs Lacroix and two other ladies and a little boy were washed ashore nine miles west of Dieppe on the Wednesday afternoon.

Edouard Lacroix travelled over to Dieppe to identify his wife. According to the correspondent of the Times newspaper who had visited the Morgue situated on the quayside he found his wife: “Draped in blankets lay … Mrs Lacroix, whose husband, having just come from England to claim her, with blanched face and closed eyes was bending down in silent agony”

Later newspapers report that, “… The remains of Mrs Lacroix … [were] brought over by the [SP] Brittany, and landed this morning [at Newhaven]. Some friends from Brighton were in waiting, and the body will be taken there for interment later on.”

Naufrage du Victoria sur les roches de l’Ailly by Théodore Albert de Broutelles. Credit : Théodore de Broutelles, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (Fonds anciens et locales de Dieppe)

The funeral of Mary Lacroix was one of the biggest Brighton had seen for many a year. One newspaper estimated the crowds that lined the route at 10,000 people. Even the circumspect Eastbourne Gazette reported that “At the cemetery there were quite 6,000 people present… The deceased was interred in the same grave as that of her son, Albert Pierre, who died last year.”

The death of Edouard Lacroix in February 1888 elicited no more than one column inch in the Brighton Gazette. It was, however, a moving comment on the family as a whole:

DEATH OF A BRIGHTON FRUITERER,- after a painful illness Mr Lacroix, senior, fruiterer of Market Street, Brighton, died on Thursday evening at his residence. It is said that one cause of his illness was the loss of his wife some time ago, after which he was never the man he was before. As a tradesman he was hard working and prosperous, and he was much respected by all who knew him.” There are no reports of crowds lining the route to his burial place.

Edouard’s executor was “Louis Victor Lacroix of 12 Bartholomews Assistant to a Fruiterer and Egg Merchant, the Son and one of the Next of Kin.”

Within three months of Edouard’s death, Louis Victor had beaten 50 other candidates to become the new Superintendent of the Police Fire Brigade. By 1891, he had moved his family to a new home at 10 Little East Street – just yards away from the market hall and his former home. Louis lost his wife Caroline in 1909. The next year, aged 61 he married 34 year old widow Inez and they moved to 15 Preston Road, a modest house just north of Preston Circus and later they moved again, just round the corner to 21 Beaconsfield Road.

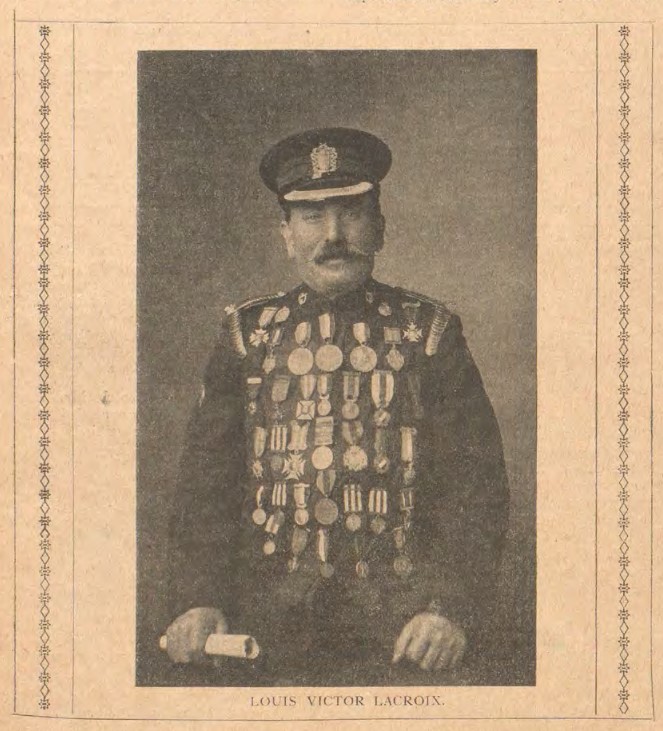

Fire Superintendent Louis Victor Lacroix in 1915. Brighton and Hove Graphic, 30 December 1915 on the occasion of a presentation to him on his 65th birthday. Image: Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

Louis Victor Lacroix was too old for active service in WW1. However, he did his best to come to the aid of not only the French speaking Belgians who flooded into Brighton. In addition he was reputed to have learned Flemish, which was the language of the majority of the refugees.

Superintendent Lacroix retired in 1922 and died, at Clamart, just 20 miles south of Paris, in 1928. The French death register gives no clue as to why he was in France – but it clearly was a county with which he had a close affinity and perhaps loved.