The talkies arrived in Brighton in the first week of July 1929 (about 10 days after they had arrived at the Rivoli in Worthing). What had been needed to get this up and running? At the Palladium on Brighton seafront “Six engineers have been engaged constantly on the task and a special screen has been provided and a new generator installed with the object of producing a picture which will give the highest satisfaction.” Mid Sussex Times of 2 July 1929. The film on offer, “The Doctor’s Secret” (1929, USA).

The Scala in Western Road. By November 1932 the cinema had been renamed Regal. Image courtesy of the Royal Pavilion and Museums Trust

Not to be outdone, the Regent Theatre in Queens Road, on virtually the same day, reopened following a “talkie” refit, with Al Jolson’s “The Singing Fool” – only three-quarters of which had sound. But sound it did have. Just to reassure patrons who did not care for such newfangled changes “silent films will be shown at the Regent on Sundays.” In fact, even mid-week, the Regent continued, every day, to show silent films at 2.25pm, 5.10pm and 8.20pm, talkies alternating with silent movies. The last show of the day was a talkie at 9.50.

In the same newspaper the Palladium countered the following week by advertising “GEORGE JESSEL (the Original Jazz Singer” in “Lucky Boy – The Greatest Singing and Talking Picture”.

The Court Theatre in New Road and the Academy in West Street had also shown talkies by October 1929. The Cinema de Luxe continued with silent films until mid-1930.

Not only were cinemas converted to enable them to show talkies. Whole rows of Georgian houses were torn down to make space for modern picture houses with all the luxury that the 1930s could afford.

Most of Gloucester Place was demolished to make place for the 1,800 seat Astoria Cinema. The Baptist Church (far right) has survived until 2024. The Astoria has not. It has been replaced by a block of flats called Rox. Image courtesy of the Regency Society

But what could you see in French? Let’s start with the French stars:

Maurice Chevalier for one. Born in 1888, he had been making silent films since 1909. Then two events coincided: talkies arrived and Chevalier was spotted by Paramount in the USA. A few of his subsequent films were made either in two version or in dubbed version – but Brighton always got the English language version.

If fans wanted to go and swoon over the heartthrob (even though by1930 he was 42 years old), the Palladium was the best place to go. Perhaps the manager was also a fan as the cinema showed most of Chevalier’s films from ‘The Innocents of Paris’ in February 1930 right through to September 1938 when ‘Break the News’ was shown. The British can take pride that the musical comedy ‘Break the News” was filmed at Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire, but many would be disappointed that René Clair, the French director, made an English film with a cast of English actors.

Another Gallic charmer was Charles Boyer.

In May 1939, just weeks before Britain went to war alongside her ally, France, Charles Boyer was heard, but not speaking French, alongside American Merle Oberon in “The Battle” (1934). He was flaunting his sexy Gallic accent at the Princes Theatre in North Street, although, to give the Astoria Cinema its due, in that same May of 1939, the cinema showed both Mayerling in March and a supporting French film called Alerte en Méditerannée (1938) starring Pierre Fresnay and Nadine Vogel. The title was even advertised in French despite many other cinemas in England merely announcing it as “Alert in the Mediterranean”. Does that say something about the relatively cosmopolitan nature of Brighton audiences? The following year, Alerte en Méditerannée was promptly remade in English at Elstree Studios as “Hell’s Cargo” – a far more dramatic title for the punters.

The “suburban” Lido (later the Odeon) near Hove station also showed Boyer in “The Battle” So the good citizens of Brighton and Hove did not get a chance to see La Bataille (1933) in which Boyer played exactly the same role, but with an all-French cast speaking French.

Charles Boyer was “big” in Brighton cinemas throughout the 1930s. Francophiles may have been drawn to the Gaity Theatre in Lewes Road in the hope that the two films on the programme for mid-May 1939 would be French. Not at all. “Algiers” (1938) starring Boyer and “The Count of Monte Christo” (1934) with Robert Donat were both American.

Then there was Danielle Darrieux. A name now largely forgotten here but a big star in Britain before and after WW2. The Astoria had been bold enough to show Darrieux’s first major film with subtitles, which was Mayerling. A few months later, the Odeon in West Street played the same film, but the Odeon was careful to point out to patrons that “The film has additional interest by reason of its French dialogue. But everyone can understand it , as there are English sub-titles”. One other French language film to star Darrieux was the costume drama, Katia (1938) again at the Astoria. Darrieux was such a major attraction that the smaller Curzon in Western Road also played one of her subtitled films.

But Darrieux, too, had flirted with Hollywood, so at the same time as her French films were being shown in Brighton, the Regent in Queens Road was showing her Universal Studios picture starring Douglas Fairbanks jnr., “The Rage of Paris” (1938).

The Curzon was very much one of the smaller cinemas. After its reopening 1932, it had just 650 seats compared to, for example, the Regent in Queens Road (3,000 by 1933) or the Savoy in East Street (2,500 seats in 1930). The manager seemed fairly committed to foreign cinema. He did not have so many seats to fill with derrières [polite translation: “patrons”] and could perhaps be more adventurous. This did not stop him laying it on the line to his patrons:

The Management have received many requests for Continental films, which, owing to certain regulations, are most difficult to book. To a very large extent, the public, by their support this week will decide whether the showing of these refreshingly novel productions will be persevered with at the Curzon. [Mid Sussex Times 2 November 1937]

The “certain regulations” the manager refers to is the 1936 amendment to the Cinematograph Films Act (1927) which, in the face of keen competition from American and even European studios, stipulated that 20% (rather than 5% in 1927) of all films exhibited in any cinema had to be British.

List alert:

Showing that November at the Curzon was a German film Liebesmelodie, a romantic musical. However, the Curzon (and its predecessor, the Regal) already had an excellent track record of showing films in French ranging from La Maternelle (1933 “The Children of Montmartre”) with 9 year-old Paulette Élambert, to the comedy with Raimu Charlemagne (nothing to do with the ninth century emperor), both shown in 1933; René Clair’s 14 juillet in 1934 and Barcarolle based on the Tales of Hoffman by Offenbach were shown in 1936.

Paris-Méditerranée a French production with French stars had been made (as many early talkies were) in two languages. In this case, French and German. Appropriately the film was shown as part of a “series of Continental films at the Regal [which] has evoked considerable interest and called forth the highest praise.” (Mid Sussex Times 10 March 1934). How odd then, that in the same newspaper item it is stressed that “The dialogue is in English but the sparkle of the French version (entitled ‘Paris-Mediterranee) has been retained in full.” An early example of dubbing, perhaps.

1938 and early 1939 were the best years for Francophiles at the Curzon as they could have seen Entrée des Artistes (1938 “The Curtain Rises”) with Louis Jouvet, Veille d’armes (1935 “In the Night Watch”) with Annabella, Orage (1939 “Storm”) with Michèle Morgan; Gribouille (1937 “Heart of Paris”) with Morgan and Raimu and La Bandera (1935 “The Enseign”) – “The dialogue is in French but there are English subtitles” the adverts proudly say.

Western Road 1935. By the small car on the left hand side, a man can be sees entering the Curzon Kinema. Image courtesy of the Regency Society

The drama Un Carnet de Bal (1937, “Life Dances On”) took some stamina from the audience of the Curzon as not only was it in the original French … it was some 2 hours and 20 minutes long.

Between the wars, French cinema had tended toward “poetic realism” and “existential gloom” (Library of Congress Research Guide). At the time, this type of entertainment was not much to the taste of British cinema audiences or even those in Brighton. Films such as l’Atatlante (1934 Jean Vigo), La Grande illusion (1937 Jean Renoir), and Quai des Brumes (1938 Marcel Carné) were not much shown outside cinema clubs and film societies.

Pépé le Moko (1937) was considered one of the great poetic realism films, so when Boyer took the title role in “Algiers”, the 1938 American remake of the film, there might have been some hope that the French flavour if not the French language would carry over. In the event, cinemagoers at the Odeon in West Street in December 1938 merely got the romantic “Algiers” “without the raw-edged, realistic and utterly frank exposition of a basically evil story” (film critic in The New York Times, 4 March 1941).

Two days before war broke out, Curzon Kinema in Western Road was showing Mayerling again and, hurrah! in the original French with subtitles which were described as “concise translations of the dialogue”. (Cinema managers in America were warned, when advertising this film,: “Do not mention that the film is French.” Would that have been a necessary warning for Brighton audiences? Maybe not.)

Apart from Mayerling and one other notable exception, all the films being screened that week in Brighton and Hove were strictly Anglo-Saxon. That exception was the German film “M” (1931) which would have been shown in a dubbed version (and which the Continentale in Kemp Town was to screen again in June 1955).

What else was there for Francophones?

There were films with tempting “French” titles such as “Moulin Rouge” (1934, USA), “Topaze” (1933, USA), based on the Marcel Pagnol play and “The Spy of Napoleon” (1936, UK), all strictly English language. Whether “Mademoiselle Docteur” (1937, UK) showing at the Odeon, West Street, Brighton in May 1938 was the original English version or the almost identical French language version (confusingly called “Street of Shadows” made at the Joinville Studios near Paris) is hard to tell from the listings. My guess is the former. The number of British and American films set in Paris was large. Virtually none were filmed in the city of light.

…

“In the event of war all cinemas will be immediately closed for two or three days”

(Home Office announcement, 31 August 1939)

The cinemas did close on 1st September. Some even closed for as long as a week. Most reopened within days.

But who would blame Brighton audiences for flocking to the Palladium in late September 1939 to see Boyer and Irene Dunn in “Love Affair” (1939). With the film’s glamour and romance, this might have been just the entertainment to get anyone through the first days of a war, phoney or otherwise.

At the outbreak of war, French cinema was flourishing… in France. In theory, the Nazi occupation starting in May 1940 should have been the end of the French industry: imported German films, pressure from the collaborationist Vichy government to make propaganda films and the exodus of the cream of French directors and performers to America. The collapse did not happen. French audiences were not, understandably, great fans of German cinema. Films from Hollywood were no longer allowed in the country. Many French directors and performers quickly learned how to “collaborate” ostensibly whilst still producing “French” cinema. Audiences for French film skyrocketed. Finance became available. French cinema survived the war. Which of those films came to Brighton? Alas, very few.

Throughout the war, comedy, romance, mystery, with a little bit of espionage, a leavening of Walt Disney and escapism, escapism, escapism was more or less what audiences wanted in Brighton and Hove. France was not forgotten however. The light-hearted “The Foreman went to France” (1942) with popular comedian Tommy Trinder, has near the beginning, an exceedingly realistic re-enactment of refugee convoys out of Paris being strafed by the Luftwaffe. According to the Mid Sussex Times it was “ the first film to be made in this country with the cooperation of General de Gaulle and the French National Committee”.

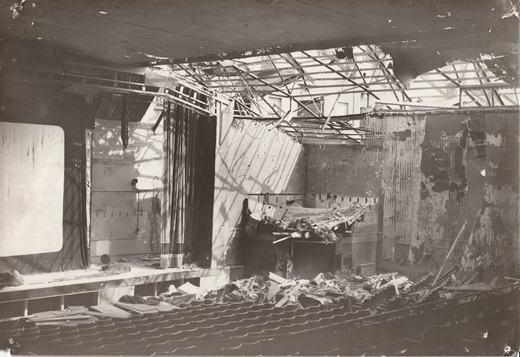

Odeon, Kemp Town. 14 September 1940. Sixteen people were killed, 10 of them children. Image courtesy of the Regency Society

The Americans did their bit for the war by making mildly propaganda films. Showing at the Savoy in April 1944, “The Cross of Lorraine” (1943) starred French movie newcomer Pierre Aumont, a Jewish actor who had taken refuge in Hollywood in 1942. The film “portrays the rigours suffered by a patriotic group of French soldiers after the invasion and fall of their country.” (Mid Sussex Times 5 April 1944)

Films continued to be British or American. The very few French films are conspicuous by their presence, for example, Amok (1934, a French language film made in Hungary) shown at the Astoria in 1941.

On VE day (Victory in Europe, 8 May 1945) Brighton cinemas were still showing a typical war-time programme with “Seven Sweethearts” at the Astoria, “Wuthering Heights” at the Brighton Curzon as well as both “Escape to Happiness” and Down Melody Lane” at the Cinema de Luxe. Would French films ever return to Brighton?

To be continued …