On a late October day a bedraggled little girl of 11 was landed on the beach at Brighton from a small wooden boat. She had witnessed insurrection in her home land. She was one of the lucky ones to have escaped.

Brighton 1785. Image © Society of Brighton Print Collectors / Regency Society

This refugee, however, had a silver spoon in her mouth. Her name was Adélaïde Charlotte Louise Eléanore d’Osmond (Adèle). The year was 1789. The start of the French Revolution.

Adèle had been born (1781) and raised in the town Versailles where her mother was lady-in-waiting at the Château to the two elderly aunts of Louis XVI.

Fortune smiled on Adèle. In her adult recollections, this is her memory of arriving in Brighton:

Nous débarquâmes à Brighton. Le hasard y fit trouver à ma mère Mme Fitzherbert. Quelques années avant, fuyant les avances du Prince de Galles, elle était venu à Paris. Ma mère, qui était sa cousine l’y avait beaucoup vue.

[By chance, my mother met there Mrs. Fitzherbert who was walking on the jetty. Some years before she had come to Paris, when avoiding the attentions of the Prince of Wales. My mother, who was her cousin, had seen a great deal of her.]

Adèle wrote her memoir when she was in her mid-50s. Her memory may have been misled by her later visits to Brighton. Budgen’s map of Brighton dated just four years earlier (1788) shows no jetty. Can Adèle be remembering the Chain Pier built much later, in 1824? Was Madame Eleanor d’Ormond (née Dillon), her mother, related to Mrs Fitzherbert. One website puts them as 13th cousins.

What a coincidence that Mrs Fitzherbert should be passing just as mother and daughter were being carried up the beach from their boat. Nearer the truth is the fact that Mrs Fitzherbert took a great interest in French refugees and often made it her duty to go to meet them as they landed. In November 1892, a group of nuns fleeing the Benedictine Convent in Montargis arrived by boat at Shoreham. Of the nuns, several were English women, one of whom was Sister Catherine Dillon who, it would seem, had met Maria Fitzherbert in Paris. However, there seems to have been little connection between the two branches of the Dillon families in the 1790s. (see also the Duchesse de Noailles and Mrs Fitzherbert)

So, in 1789 Adèle and her parents stayed with Mrs Fitzherbert. Mrs Fitzherbert and the Prince of Wales habitaient en simple particuliers, une petite maison à Brighton. [lived as private individuals in a little house in Brighton.]

That petite maison was the Marine Pavilion, recently improved and enlarged by Henry Holland. Adèle was not overly impressed. Her older self admits that her younger self was a bit of a snob. The palatial Burleigh House had not impressed her either: j’étais trop accoutumée à voir de grands établissements pour en être frappée. [I was too accustomed to magnificence to be greatly impressed.]

The Marine Pavilion in 1788. Image © Society of Brighton Print Collectors / Regency Society

Young Adèle was, however, impressed by the pretty baubles she was shown at Mrs Fitzherbert’s:

Je me rappelle avoir été menée un matin chez Mme Fitzherbert, elle nous montra le cabinet de toilette du prince, il y avait une grande table toute couverte de boucles de souliers. Je me récriai en les voyant et Mme Fitzerbert ouvrit, en riant, une grande armoire qui en était également remplie. Il y en avait pour tous les jours de l’année.

[I remember one morning being taken to Mrs. Fitzherbert’s house, and her showing us the Prince’s dressing-room, where there was a large table entirely covered in shoe buckles. I expressed my astonishment at the sight, and Mrs Fitzherbert, with a laugh, opened a large cupboard which was also full: there were enough of them for every day of the year.]

The period between 1790 and 1815 were politically tumultuous for the French; during that time, they managed to get through the first Republic (including a bloodbath thanks to Madame Guillotine), the first Napoleonic Empire , the Battle of Waterloo and finally the Restauration (Louis XVIII, 1815-1830). The d’Osmond family were buffeted from safe country to safe county until at last, at the restauration of the monarchy, Adèle’s father was appointed French Ambassador to the Court of St James in 1815.

Adèle had married the adventurer General Benoît de Boigne in 1797. She was 16, he was 46 … and he was raring to get back to his adventuring. Which he promptly did. Adèle remained with her parents until their deaths in the 1830s.

Adèle D’Osmond by Jean-Baptiste Isabey, 1810 Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1818, Adèle was back in Brighton. The Prince of Wales had married. The Prince’s daughter Charlotte had married … and recently died in childbirth. Adèle had met, briefly, Princess Charlotte during the latter’s pregnancy. As Adèle points out : la mort vint enlever en une seule heure deux générations de souverains : la jeune mère et le fils qu’elle venait de mettre au monde. [Within the space of one hour, death carried away two generations of sovereigns: the mother and the son to whom she had just given birth.]

Adèle recounts that on her next visit to Brighton in 1818, everyone from the highest to the lowest was in mourning. This had put a stop to concerts and balls. She then continues with the slightly barbed comment:

Le deuil encore récent pour la princesse Charlotte ne permettait pas les plaisirs bruyants à Brighton, mais les regrets , si toutefois le Régent en avait eu de bien vifs, étaient passés, et le pavillon royal se montrait plus noire que triste.

The recent period of mourning for Princess Charlotte did not permit of any boisterous pleasures in Brighton, but the Princes’ grief, if he had indeed felt any very strongly, was past, and the mood in the royal pavilion was gloomy rather than sad.

Now nearly in her 30s, Adèle was impressed with the welcome from the Prince Regent. The Prince had sent his Maître d’hôtel to ascertain in advance what his guests liked and disliked. Adèle continues:

Il est impossible d’être un maître de maison plus soigneux que le Régent et de prodiguer plus de coquetteries quand il voulait plaire. Lui-même s’occupait des plus petits détails.

[It is impossible to be a more meticulous host or to lavish more niceties than did the Regent when he wished to please. He saw to the smallest details personally.]

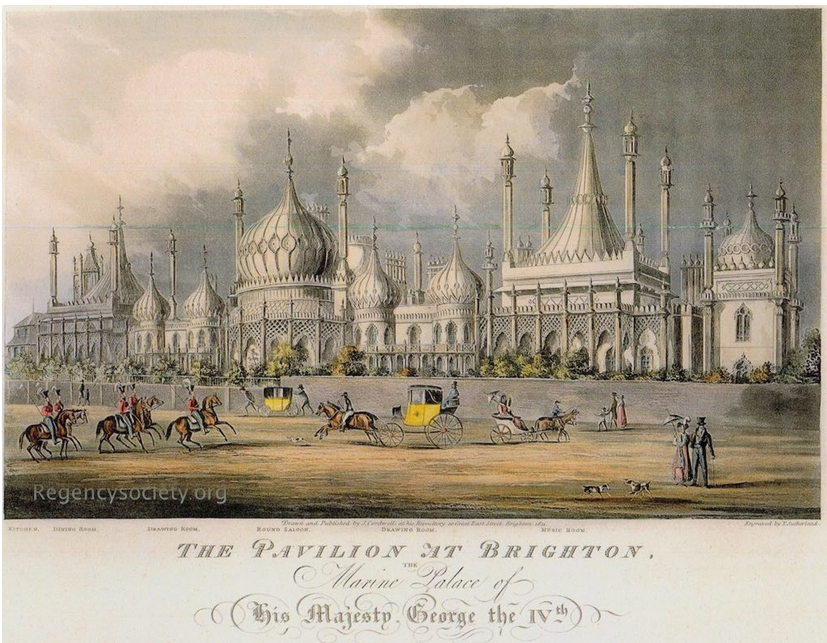

Adèle certainly does not pull her punches. In the very next line of her memoir she states categorically of the recently Nash reconstruction: Ce pavillon était un chef d’œuvre de mauvais goût. [This pavilion was a masterpiece of bad taste]. She goes on to criticise la dispendieuse élégances [the extravagant elegance] of the rebuild as well as the jumbled nature of the various elements of this bizarre et laid palais. [strange and ugly palace.] But she found the place amusing and seems to have enjoyed looking at all the strange curiosities she found in the palace.

The Roayl Pavilion in 1821. © The Society of Brighton Print Collectors / Regency Society

If staying in the Pavilion, the guest’s room would be fitted out exactly to their taste; despite the circumstances, some music was allowed in the evening. The music, played only in the entrance hall, was not to Adèle’s taste. It was horns and other noisy instruments that the Prince liked. Did the Prince rather irritate Adèle? Le prince y prenait grand plaisir et s’associait souvent au gong pour battre la mesure. [The Prince delighted in the music and often accompanied the musicians by beating time on the dinner gong.] That certainly could get very wearing.

We can perhaps sympathise with Adèle when she says that evenings with the Prince were entertaining merely because he was a prince. Had he been a commoner, such evenings auraient paru assommantes [would have appeared deadly dull.] All the more so as they went on until two or three o’clock in the morning.

Life at the Pavilion must have seemed somewhat monotonous as Adèle records : Pendant la semaine que nous passâmes à Brighton, la même vie se renouvela chaque jour. C’était l’habitude. [Throughout the week we spent at Brighton, the same daily round was repeated every day. It was the routine.] That routine was quite simply the following: the Prince appeared in public at 3pm. He went for a ride. He returned to the Pavilion via a short spell with his next door neighbour (who at the time was Lady Hertford, his current mistress). Back home to dress for dinner and then one of those interminable evenings.

Lady Hertford was thought to have been instrumental in turning the Prince from the Whigs to the Torys. Image courtesy of the Royal Pavilion & Museums Trust

On her first morning at the Pavilion, Adèle was most surprised to find that breakfast was served sur le palier [on the landing]. She was astounded by the magnificence of the palier, of the silver and the chinaware – not to mention the profusion of carpets, armchairs, porcelain and dishes, everything, in fact, that good taste and luxury could provide. Adèle was rather amused to find that, despite the exquisite refinement of the meal, the Prince himself never partook of it.

The South Gallery, Royal Pavilion, Brighton. Drawing by John Nash, 1826. Image courtesy of Royal Pavilion & Museums Trust.

Despite being somewhat bored, Adèle clearly did not blot her copy book as she was invited again the following year. But in 1819 Adèle’s father lost his post as French Ambassador and the family returned to France.

Adèle was an anglophile. Many of her letters in French are scattered with words and expressions in English. She visited England many times later in life, but never, alas, never again wrote of any visit to Brighton.